Matthew Ellis, Staffordshire Police and Crime Commissioner first put the issue of mental health and its impact on policing on the national stage several years ago. Progress has been made since then by Staffordshire Police in reducing the number of times cells are used as a so-called ‘place of safety’ for those in mental health crisis. But Mr Ellis is concerned the issue has just shifted elsewhere in the system and is still having a huge day to day impact on policing.

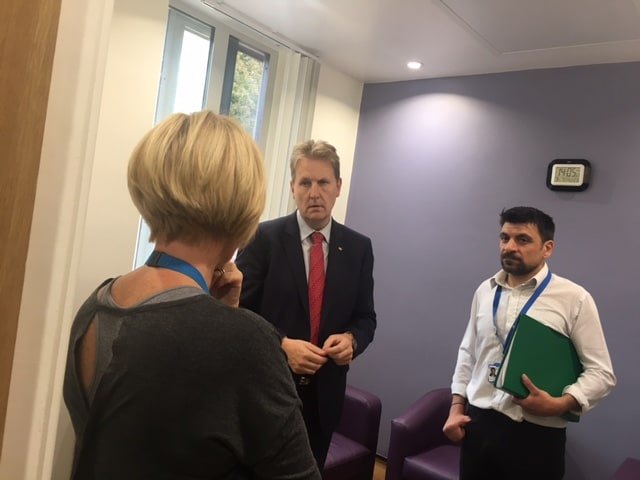

To get the full picture, the PCC is undertaking a fact-finding tour of mental health facilities in the county. Last week he visited a unit at St George’s Hospital, Stafford and today, he will be at Harplands Hospital in Stoke-on-Trent.

Mr Ellis has also called an urgent meeting of health professionals to discuss the matter on Wednesday night at Staffs Police HQ in Stafford.

Here’s an article which outlines the PCC’s concerns;

Mental ill-health and policing – what’s the true picture?

I must confess that before being elected as Staffordshire’s Police and Crime Commissioner it wouldn’t have occurred to me that mental health issues and policing are quite so inextricably linked.

Less still would I have imagined that in the UK, in 2013, society would be routinely placing individuals with mental health issues in police cells when no crime had been committed, simply because there were no appropriate healthcare facilities available.

I admit that is a somewhat simplistic view of an immensely complex subject. After all, if I was walking down the street and saw someone distressed, acting irrationally or potentially putting themselves in harm’s way, I too would call the police in the first instance.

The urgency of that situation probably means they are needed initially but once things are under control the police are not equipped, nor best placed, to take responsibility for that person for any longer than is absolutely necessary. They need healthcare support and too often people can even end up criminalised in the justice system when they shouldn’t be.

In 2014 I kicked off work to understand the scale of the issues police faced. The ‘Staffordshire Report’ provided detailed analysis over an eight week period of all police incidents involving mental health. It illustrated, case by case, the human aspect and the pressures on police officers, often in the middle of the night, dealing with individuals who have some sort of mental health condition.

It found 15% of total police time here was spent dealing with mental health related incidents. Wellbeing of all individuals is paramount to policing but it is not wholly unreasonable to question the thousands of hours of police time spent supporting people in that situation when other services should be.

New thinking, extra investment from my office and renewed effort across all agencies since then means that the number of individuals ending up in custody in those circumstances has reduced by over 80% in Staffordshire. Our work also stimulated other areas to focus on this very human and very practical issue as well as catching Government’s interest, resulting in new laws, joint concordats and national action.

I am the first to praise Staffordshire Police, healthcare professionals and everyone involved in achieving the goal I set which was to substantially reduce the number of people ending up in a cell who shouldn’t be there. In short using police custody as a ‘place of safety’ because no healthcare facilities are available now happens less here, and also across the country.

However, whilst this is genuine progress the situation may not be quite as it seems. The challenge for policing in relation to incidents involving mental health is much wider than simply the custody issue. At the sharp end, officers are still saying with certainty that they spend more time than ever dealing with incidents involving some aspect of mental health. So what is going on?

The lack of consistency locally and nationally around what constitutes a mental health associated police incident is not helpful. Not being clear about the length of time police officers spend dealing with each incident involving mental health may well be masking an even more complex picture.

The evidence suggesting police officers often spend hours waiting in A&E with people in their ‘care’ or comforting individuals in distress, is compelling. Not relying on police cells, as happened historically, is a big and humane step forward but it’s clear that officers are regularly going beyond their responsibilities, and expertise, by spending policing time filling gaps in some other public services

I’ve seen first-hand that collaborative working between police and health agencies has improved, no question on that. Although that does vary geographically across Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent. Police are also now better trained to recognise mental ill-health and whilst the availability of crisis care beds is generally better now in Staffordshire that too varies geographically.

The wider pressures on policing are growing because of societal change, threats that emanate from countries far away and new types of crime in an internet connected world. It means our police have little or no capacity to pick up extra responsibilities that other agencies should be dealing with.

Understanding wider issues around the increasing number of young people suffering mental ill-health, the impact of so called legal highs and the widening spectrum of social and practical pressures that are often labelled mental health is crucial to policing and our society.

All this feels a bit déjà vu. It takes me back to 2014 and to me it is clear that a new piece of work is needed to update the one I commissioned back then. That will start soon and I’m also hosting a meeting of mental health professionals and leaders where I expect discussions to be honest all round, forthright and informative.

It is so important that society continues to accept and embrace the challenges mental health brings to all ages and all backgrounds. The signs are there in relation to understanding and being compassionate towards this highly complex, very human area of public work, but they ebb and they flow.

To deal better with the lasting problems that the mix of mental health, policing and criminal justice can bring we must have a true and comprehensive picture. I am hopeful that part two of the work I kicked off in 2014 will help once again to provide that.